Council of Fifty in Nauvoo, Illinois

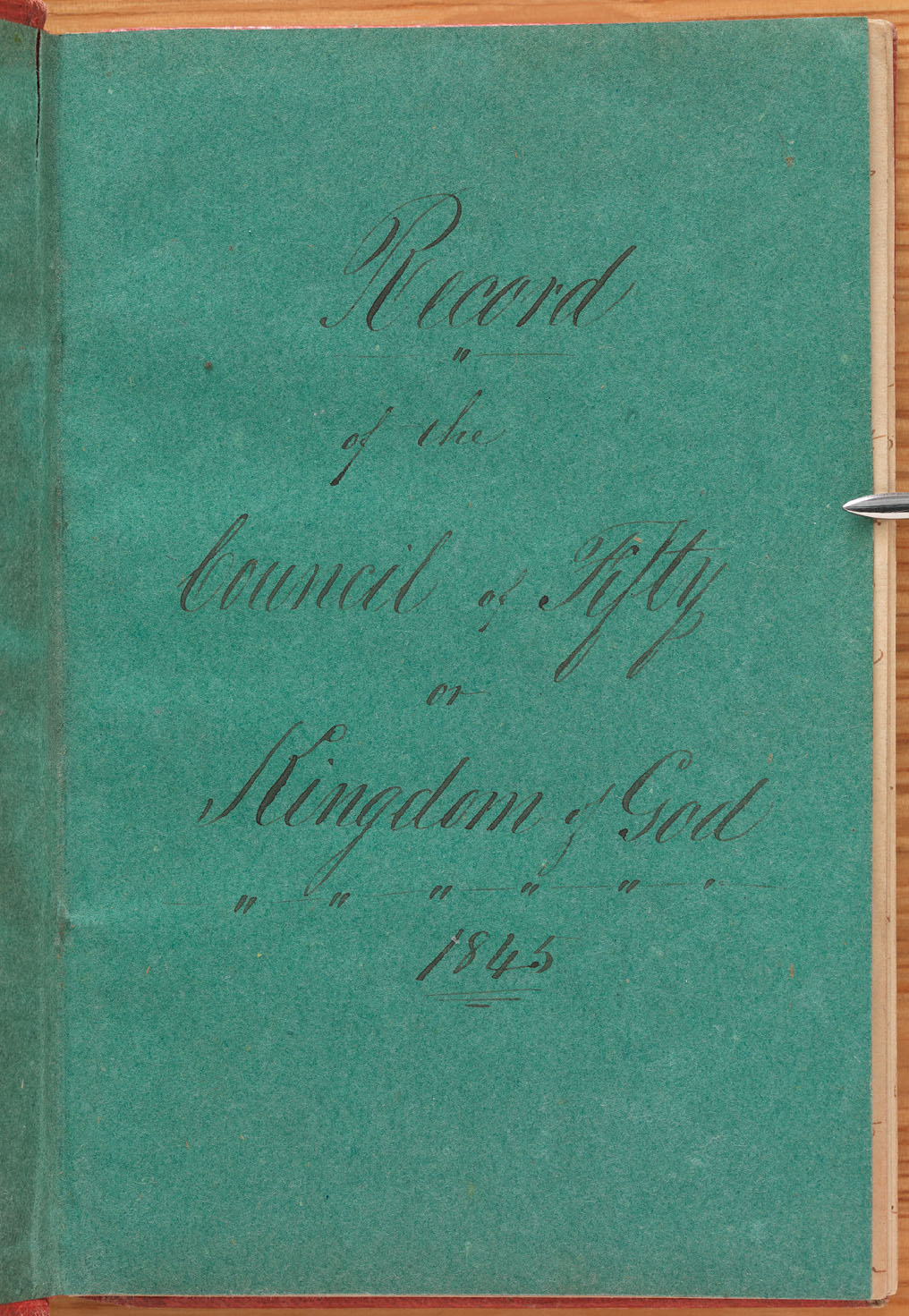

Nauvoo Council of Fifty record. William Clayton, the first clerk of the Council of Fifty, kept the minutes of the Nauvoo-era council meetings and copied them into three small blank books.

In September 2016, the Joseph Smith Papers Project, an official project of the Church History Department, published the minutes created in Nauvoo, Illinois, of a lesser-known Church organization called the Council of Fifty. Joseph Smith formed this council in March 1844. The council met fairly regularly from then until January 1846, and then it functioned intermittently during a handful of years in Utah until the 1880s. The publication of the Nauvoo-era minutes of this council is another step in the Church History Department’s ongoing effort to publish all of Joseph Smith’s papers.

Because these minutes have never been open to research, this publication is expected to generate significant attention from the media and historians. The following article answers some of the most common questions Church members may have about the Council of Fifty. For additional information, see the new publication, Administrative Records: Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846.

Where Did the Minutes for the Nauvoo Council of Fifty Come From?

William Clayton, an English convert who began doing clerical work for Joseph Smith in 1842, was appointed clerk to the Council of Fifty at the council’s first meeting in Nauvoo. Clayton kept meeting minutes on loose sheets of paper and later copied these minutes into three small bound volumes. These volumes were brought across the plains to the Salt Lake Valley by Brigham Young, and they were retained by him and other members of the council. By the 1880s, the volumes were in the custody of the Office of the First Presidency, where they remained until the 21st century. In 2010, the First Presidency transferred the volumes to the Church History Library, after which Joseph Smith Papers scholars began preparing the records for publication.

When and Why Was the Council Formed?

The impetus to form the council came when Joseph Smith received two letters in Nauvoo on March 10, 1844, from Church members involved in logging operations in Wisconsin Territory up the Mississippi River. Since their assignment to produce lumber for the Nauvoo Temple and the Nauvoo House (a hotel) was nearing an end, these members proposed to relocate elsewhere, possibly to Texas, which was then an independent republic and not part of the United States. The Wisconsin Saints hoped to raise money for the Church in Texas and spread the gospel among American Indian tribes.

After discussing the letters on March 10, Joseph Smith and other Church leaders met again on March 11 and formally organized a council with 23 initial members. Though the March 11 minutes are unfortunately lacking in detail, it appears that the proposal to establish a settlement in Texas led to discussions about the desire to create a theocracy—a government in which Church leaders would also have political power.

According to the minutes, “All seemed agreed to look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.” The council was formed not only to plan a new settlement, however. The members of the council saw the council’s formation as the beginning of the literal kingdom of God on earth and anticipated that the council would “govern men in civil matters.”

Why were Church leaders so enthusiastic about establishing a settlement outside the United States, and why did they want to form a new kind of government? Perhaps the primary reason for this interest was the persecutions the Saints had experienced in Missouri in the 1830s. The Saints had been driven from Jackson County in 1833 and then completely expelled from Missouri in 1838–39 under order of the Missouri governor. The Saints repeatedly sought protection and redress through legal means but were largely unsuccessful. These experiences left them deeply convinced that state and local governments were unable and unwilling to protect the rights of unpopular religious minorities.

At this time, the United States Bill of Rights protected against abuses only by the federal government, not state and local governments. That meant that federal officials generally refused to intervene to protect rights at local levels. Like abolitionists and members of other maligned movements who had suffered at the hands of majority opinion, Latter-day Saints sought changes that would restore what they saw as a proper balance to America’s political system.

Joseph Smith and others had designed the city of Nauvoo’s government to provide protections the Latter-day Saints had lacked during the 1830s; the Nauvoo municipal charter, granted by the state of Illinois in 1840, was intended to guard against many of the institutional wrongs the Saints had experienced. For example, the charter authorized the creation of a separate militia (the Nauvoo Legion) and gave the Nauvoo city court far-reaching authority, which the Saints used to protect themselves from what they perceived as unjust legal actions.

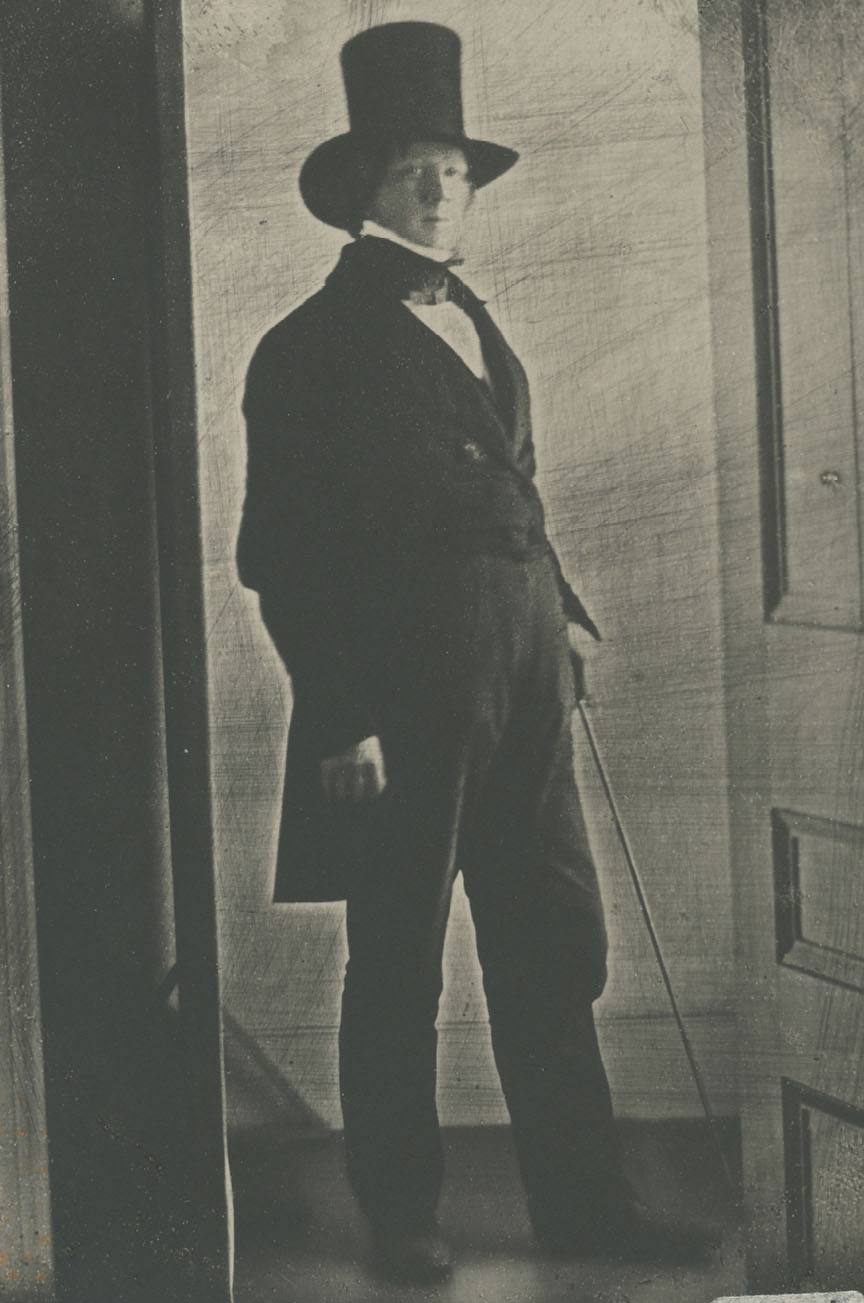

After failing to receive assurances from any of the expected main candidates in the 1844 presidential election that the Saints’ rights would be protected, Joseph Smith declared his candidacy for president of the United States in January 1844. His platform emphasized, as do his remarks in the Council of Fifty, a commitment to protect the minority rights of all, not just Latter-day Saints, against the tyranny of the majority.

By March of that year, significant opposition was growing toward the Church in and around Nauvoo, in part because of the practice of plural marriage and the Saints’ growing political power. Members of the Council of Fifty were drawn both to the possibility of relocating significant numbers of Saints outside of the United States, where they could create their own government, and to the possibility of creating a better form of government within the United States.

Though council members generally used the term theocracy to describe what they viewed as an ideal form of government for the kingdom of God, their model also incorporated democratic elements. They believed that a “theodemocratic” government would protect the rights of all citizens, allow for dissent and free discussion, involve Latter-day Saints and others, and increase righteousness in preparation for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Joseph Smith explained that a “theocracy consisted in our exercising all the intelligence of the council, and bringing forth all the light which dwells in the breast of every man. . . . Theocracy as he understands it is, for the people to get the voice of God and then acknowledge it, and see it executed.” Because council members anticipated that Joseph Smith would serve as both the religious and political leader of the government of the kingdom of God, they chose him at the council meeting on April 11, 1844, to be their “Prophet, Priest & King.” Council participants understood that this action would have no immediate political consequences.

How Did the Council Relate to the Church?

Though general and local Church leaders were central to founding the Council of Fifty and were involved with the council throughout its existence, the council was not an ecclesiastical body. The First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the other Church quorums and councils continued to function as normal and continued to be responsible for ecclesiastical matters such as appointing officers, disciplining members, teaching doctrine, and performing ordinances. The Council of Fifty, in contrast, was a temporal or political body created to protect the Church and provide it space to flourish.

As Joseph Smith explained to the council in April 1844: “There is a distinction between the Church of God and kingdom of God [or Council of Fifty]. The laws of the kingdom are not designed to effect our salvation hereafter. It is an entire, distinct and separate government. The church is a spiritual matter and a spiritual kingdom; but the kingdom which Daniel saw was not a spiritual kingdom, but was designed to be got up for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”

How Did the Council Get Its Name?

On March 14, 1844, a revelation gave the official name of the council: “The Kingdom of God and his Laws, with the keys and power thereof, and judgement in the hands of his servants.” Council members often used an abbreviated form of this name, such as the “Kingdom” or “Council of the Kingdom of God.” After the council reached a membership of 50 men on April 18, 1844, Joseph Smith declared the council “full.” Thereafter, it was often called the Council of Fifty.

Who Belonged to the Council in Nauvoo?

Membership remained at roughly 50 throughout the council’s existence. Most of the members were prominent Church leaders, such as members of the Twelve and bishops. Joseph Smith admitted three men who were not members of the Church to the council, explaining that “we act upon the broad and liberal principal that all men have equal rights, and ought to be respected, and that every man has a privilege in this organization of choosing for himself voluntarily his God.”

What Did the Council Accomplish during the Nauvoo Era?

At the practical level, the Nauvoo-era Council of Fifty had perhaps three primary accomplishments. First, the council helped manage Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign. Second, the council provided a forum for making practical decisions about matters in Nauvoo, including construction of the Nauvoo Temple and how to protect and govern the city after the state of Illinois repealed the Nauvoo municipal charter in January 1845. Third and most important, the council played a major role in exploring possible settlement sites and in planning the Church’s migration to the American West.

What Can Latter-day Saints Today Learn from the Minutes of the Nauvoo Council of Fifty?

The minutes of the Council of Fifty provide a way to study how Church members can make decisions according to inspiration and the council process. While the council chairman (Joseph Smith or Brigham Young) directed council discussions, the members had equal opportunity to speak, and council decisions were to be unanimous. Much of the council business was delegated to committees of a few council members who studied assigned matters separately and returned to the council with recommendations that were then considered by the whole group.

Council members believed they had an obligation to offer candid commentary on issues presented before the council and that their collective deliberations would lead them to correct decisions. From the beginning of the council, Joseph Smith urged participants to “speak their minds” and “to say what was in their hearts whether good or bad.” He said he “did not want to be forever surrounded by a set of ‘dough heads’ [unintelligent people] and if they did not rise up and shake themselves and exercise themselves in discussing these important matters he should consider them nothing better than ‘dough heads.’”

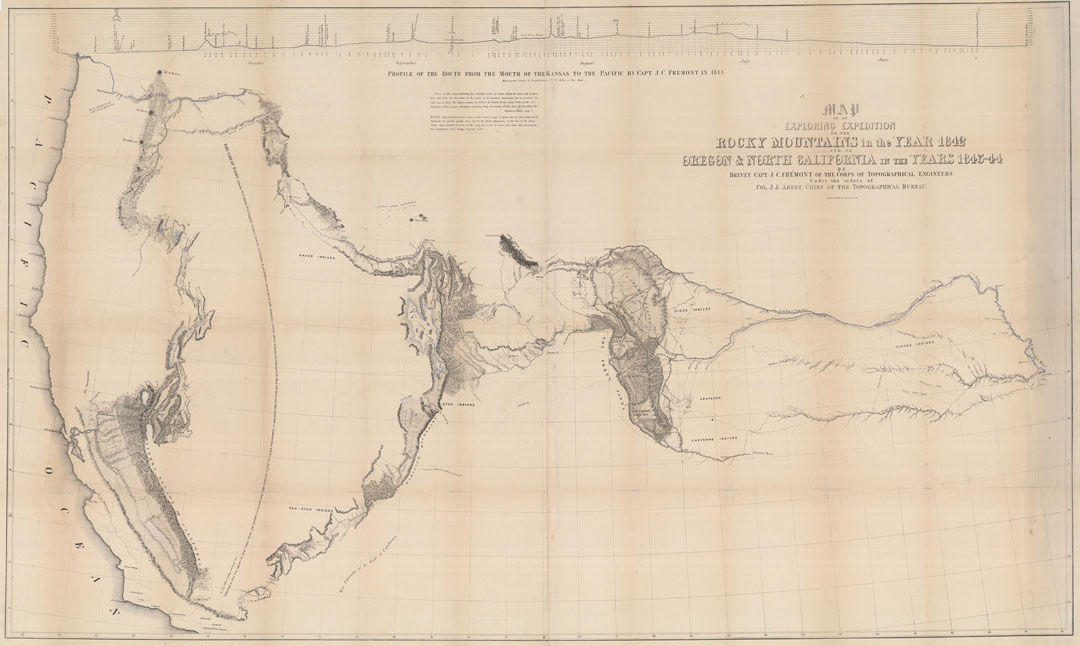

This deliberative process was followed, for example, as the council explored possible new settlement sites for the Saints. Council members initially suggested a broad range of sites, including Texas, California, Wisconsin, Oregon, and the Rocky Mountains. Over the course of many months, the council studied the latest maps and reports of explorations and sent out men to gather as much information as possible and to seek possible political alliances. As new information came in, the council eliminated possibilities that were impractical.

Eventually the council began to focus on the Rocky Mountains and then the valley of the Great Salt Lake as the destination. Throughout this process, council members felt that they were being guided by revelation, but not until the time for departure neared did Brigham Young feel confident of the exact destination. On January 13, 1846, as the Saints were preparing to leave their homes in Nauvoo, Brigham Young declared, “The Saying of the Prophets would never be verified unless the House of the Lord should be reared in the Tops of the Mountains & the Proud Banner of liberty wave over the valley’s that are within the Mountains &c I know where the spot is & I no [know] how to make the Flag.”

The minutes also contain many previously unknown statements from Joseph Smith and other Church leaders. On May 3, 1844, Joseph Smith taught the council, “We should never indulge our appetites to injure our influence, or wound the feelings of friends, or cause the spirit of the Lord to leave us. There is no excuse for any man to drink and get drunk in the church of Christ, or gratify any appetite, or lust, contrary to the principles of righteousness.”

Amasa Lyman, a counselor in the First Presidency, stated that he looked “for a full and perfect emancipation of the whole human race, that the sound of oppression should be buried in eternal oblivion. The paltry considerations of earthly gain and glory falls into insignificance before the glories we now realize. The object we have in view is not to save a man alone or a nation, but to call down the power of God and let all be blessed, protected, saved and made happy—burst of the chains of oppression. This is a kingdom worth having.”

On one occasion, Brigham Young instructed the council on how Church leaders receive revelation. God spoke according to the understanding of His servants. Brigham taught that “there has not yet been a perfect revelation given, because we cannot understand it, yet we receive a little here and a little there. [I] should not be stumbled if the prophet should translate the Bible forty thousand times over and yet it should be different in some places every time, because when God speaks, he always speaks according to the capacity of the people.” Furthermore, God had much yet to reveal to the Latter-day Saints. Brigham commented that he did “not know how much more there is in the bosom of the Almighty. When God sees that his people have enlarged upon what he has given us he will give us more.”

Perhaps the most powerful teaching in the entire record of the Nauvoo Council of Fifty is Joseph Smith’s statement on religious liberty from the April 11, 1844, meeting. Arguing that the agency God gave His children requires mortals also to grant and safeguard the freedom of religion, Joseph Smith declared: “God cannot save or damn a man only on the principle that every man acts, chooses and worships for himself; hence the importance of thrusting from us every spirit of bigotry and intolerance towards a mans religious sentiments, that spirit which has drenched the earth with blood— When a man feels the least temptation to such intolerance he ought to spurn it from him. It becomes our duty on account of this intolerance and corruption—the inalienable right of man being to think as he pleases—worship as he pleases &c being the first law of every thing that is sacred—to guard every ground all the days of our lives. I will appeal to every man in this council beginning at the youngest that when he arrives to the years of Hoary age he will have to say that the principles of intolerance and bigotry never had a place in this kingdom, nor in my breast, and that he is even then ready to die rather than yield to such things. Nothing can reclaim the human mind from its ignorance, bigotry, superstition &c but those grand and sublime principles of equal rights and universal freedom to all men. . . . When I have used every means in my power to exalt a mans mind, and have taught him righteous principles to no effect—he is still inclined in his darkness, yet the same principles of liberty and charity would ever be manifested by me as though he embraced it. Hence in all governments or political transactions a mans religious opinions should never be called in question. A man should be judged by the law independent of religious prejudice.”

Footnotes

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]